Complex Systems in Football

Pep Guardiola : “Football is not A, B and C, what works last season will not necessarily work this season. What did not work last season, could work now. It is open, it is moving, it is like an animal, it develops. Sometimes it moves this way, sometimes it moves another way.”

“It is open, it is moving, it is like an animal, it develops.”

Pep phrases this in an interesting way. He is describing the characteristics of a complex system.

He is probably referring to tactical trends, whether adding a pure 9 in Haaland, or a dynamic strikerless front 3, teams find ways to score using different approaches. Trends in how teams line up alter over time.

This applies to the wider definition of football clubs too. They are also complex systems.

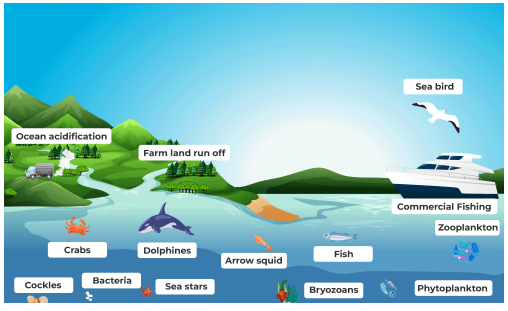

Complex systems are systems composed of many components that interact with each other. The economy or the natural world are examples of such systems.

Modelling such systems is difficult. We know that changing inputs will have an impact on the output but we can’t know for sure because of the multiple interactions that occur.

Even in the most basic ways we can see this in football. If you take out De Bruyne for Doku you aren’t just swapping two attacking midfielders. You are removing a great passer, but gaining speed and dribbling. You can’t expect them to play in the same way, and the players around them will change what they do to make the best use of the skill-sets on the pitch around them.

Adaptation is key to understanding complex systems. The change in the system was one player for one player, but the impact was felt at many levels. As individual players they understood that adjustments had been made, maybe they need to play passes, maybe the fullback needs to overlap less or make more inverted runs.

Could we model how the change impacted City’s likelihood of scoring a goal? There are threat/on ball value models that can show what a player generally does. However there are a lot of factors that change that likelihood in a specific game. Maybe the fullback is scared of direct 1v1 running, or lacks pace. If Doku is up against that player then his expected output is probably higher than against a generic PL defender.

Another feature of complex systems is critical transitions. This means that there is a tipping point where a system goes into failure. Take our well-functioning team. The goalkeeper goes off injured, but there is no replacement on the bench, only one element of the system has changed but the impact is critical. Suddenly a non-specialist has to go in goal, the team changes shape (adaptation) to try and limit the number of shots against but every chance conceded is now far more likely to result in a goal against.

Football teams also fit the nested criteria of a complex system. We have a team that is a complex system in itself, made up of players, and each player is a complex system, where their performance levels are influenced by many factors (physical, psychological, environmental).

The performance of a football team is also emergent. This means that players interact differently when together than they would individually. A good example is Alphonso Davies, a left-back for Bayern Munich but an attacker for a national team, his ability is valued differently in different contexts. A head coach working with a group of players will often try different systems to see the best way they can work with them to produce the best results.

Non-linear (butterly effect) impacts are common in football, a small change can have an outsized impact. A missed opportunity can lead to a defeat, which can lead to a sacking of a coach, which can lead to a player being sold, which can lead to a new player signing, who scores 30 goals, and is sold for £50m etc etc

And finally, feedback loops are part of complex systems. We may call it momentum in football, we win some games, better players want to join, we sign them, we win more games, players enjoy winning and focus more on the right preparation which enables a better chance to win each game.

How to work with complex systems

So if we agree these systems are complex then how does that change how we work within them?

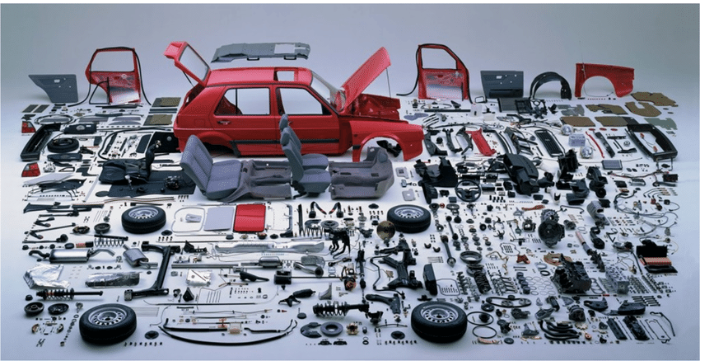

The usual approach is to look at the system as a collection of individual parts. We usually then focus on the coaches and the players and assign blame for failure onto one (or more) of them.

This is sometimes referred to as a reductionist approach.

Even if we appreciate it is a complex system, we identify one part of the system and assume by changing that part we will improve the whole.

However in football, and other complex systems, we don’t really know how much of the success or failure is reliant on each individual input.

And even if we change that person (input) we rarely do so in isolation and without changing many other factors at the same time.

In a complex system we see the football club as being more than just the sum of its parts.

Ceteris Paribus and the problem with measuring output

Ceteris Paribus means “all else remaining equal” and is an important method for testing impact. For example if we sign a new striker ceteris paribus how many more goals would we forecast for the team next year?

We can certainly guesstimate based on factors like their xG performance, the number of shots they generate per game, the creativity of the players in our team in terms of xA.

But football teams are dynamic, they change more than just one player in almost every game, over the close season a team usually changes 3-6 starting players. You can never run a controlled experiment.

We can work with generalities but they always seem a bit lame. Saying “typically strikers who take more shots score more goals” is not going to win you many friends in a recruitment meeting where you have to be a bit more definitive to be of any real value.

What we like to do is look at the mechanisms by which the team could score goals. How will the ball get into attacking areas? What sort of attacking output do we need from our wingbacks? What type of shots do the attackers tend to take? Are they creating for themselves or reliant on crosses or through balls? Is there enough variety in the way we create?

These type of conversations are too rare in football, let alone attempts to quantify them

So what can we do?

The most important way to work with complex systems is to define the desired output.

For an economy that may be a growth rate of 3%, for an ecosystem it may be for the amount of wildlife to increase, for a football team it may be to win promotion.

You can then list the factors you know contribute to the likelihood of that output being achieved. And conversely the factors that will prevent you succeeding.

Some of these will be controllable and some not.

What comes next is strategic planning.

Most clubs don’t have a strategy. They have a list of desired outcomes but not actually a plan.

You take the list of things that you know makes you more likely to succeed and that you can control and you work out how to do them better than everyone else.

As an economist you know that you cannot do anything immediately about negative energy supply shocks (War, a cold winter) leading to a much higher cost of importing fuel and a large external flow of money leaving the economy. But you can forecast that this is likely to happen and invest in a domestic energy supply with potential export capacity.

Likewise in football you can’t control the prices of good young players increasing significantly due to high competition from newly acquired clubs. What you can do is look at ways to secure players earlier through an academy or partner club abroad.

None of this is easy, they are long term projects that will almost certainly be threatened with closure and written off as failures before they start to produce any impact.

Methodology for measuring

Most clubs now use xG to measure how well they are performing.

There is a certain amount of nuance required in interpreting xG but it gives a good guideline for whether teams are generally creating better opportunities than their opponents.

However xG is measuring the output on the field. Not the quality of the inputs.

We can use a reductionist approach to break down the inputs but the answers can be complex.

For example is a lack of shots due to poor supply or poor movement or a mismatch between players, or a lack of fitness, or bad coaching.

Micro or Macro

We can go through micro reasons for each of these and analyse how to improve them.

Ultimately they will all go back to the more macro fundamental points of needing the best players you can get, coached well and as fit as possible, playing in a system that suits them.

We work from the principle of the more data the better. We need to be able to measure progress against the macro aims by studying the micro data.

Quick fixes and root causes

We can certainly identify and measure that things are or aren’t working that well.

But we need to identify root causes.

In ecology we might notice the output that there are not many water birds in the park. We can bring some more in but they fly away, the fundamental problem is a lack of fish. Add fish? They all die off, and that is because the water isn’t clean enough. Finding a solution to clean the water solves the fish and bird problems but required a different approach.

In football that might mean that our wingers are good, our strikers are good, but neither are getting the ball as our defenders and midfielders can’t retain possession.

This requires granular detail and a mindset very different to most clubs.

Sometimes there are quick fixes. It can be as simple as one “bad apple” but if you don’t know what you want the system to look like then it is hard to identify the factors that are inhibiting success.

Infinite game and sugar highs

The easiest thing to do in football is spend other people’s money.

Opportunities are short lived, if you do badly you may never work again, if you are perceived to have done well you can quickly earn a lot of money.

An employee will always be motivated towards short term success. Clubs show no loyalty in general, and receive little in return, contracts are short.

Clubs live off sugar highs, where money is spent on short term cycles aiming for immediate success.

This is why long term thinking and planning has to be a function of ownership not sporting staff.

The “infinite game” part of football is particularly important given the complexity of the sport. Almost everything that can increase the long term capacity of clubs to perform better takes multiple years to come to fruition.

Maybe we are idiots

A finishing quote from Bill Shankly “Football is a simple game complicated by idiots”

I think there is something in that, we often talk about alignment in football clubs.

A relatively small number of people who are aligned can have a huge impact on a club.

When you find aligned people they see things the same. They instinctively know what they other people would do and what they are trying to build.

When you find people who just “get it” (by which I mean agreeing entirely with the way you see things) and things are going well you sometimes look at other clubs and think “What are they doing? This is easy”

Then when you see unaligned clubs, or where the complex system that is a football club starts to fail, you realise how difficult it can be when there are fundamental mismatches between how people see things and how they want to build a football club.

After 5 years and 30+ clubs we have seen a lot of ups and downs, but are more confident than ever that ownership strategy backed by quantitative information (data analytics) and insights derived from it, combined with long term thinking is what makes clubs succeed.

Leave a comment